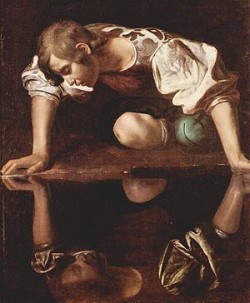

Narcissism and Nobility

Meditations on 1Corinthians

A Letter for Our Times; A Letter for Us

1 Corinthians 1.1-9

Why 1Corinthians?

The book of 1Corinthians is about what it means and what it takes to be Christ’s church, his people, in the midst of a powerful and pervasive culture operating on completely different values, motivations, and goals – in short, a completely different faith. There is hardly a more appropriate book for Christians in America to consider at this time, for we find ourselves in a very similar situation.

(Note: Information about ancient Corinth and the Corinthian church is derived from 1 Corinthians by David E. Garland pp. 1-36.)

Land of opportunity.

Like America, Corinth was considered a land of opportunity, a place which had no aristocracy to keep everyone in their proper station, a place where one had the chance to make one’s own fortune, to make a name for oneself. Like America, Corinth rose quickly from humble circumstances to great heights – heights superior even to iconic Athens, just 50 miles away.

A glitzy melting pot.

By the time Paul founded the Corinthian church circa AD50, Corinth was a melting pot of people, and she was famous, even as modern America increasingly is, for wealth, glitz, immorality, and narcissism. One of its temples had 1000 temple prostitutes. Combine Hollywood and San Francisco and you’ll begin to get the picture. While Corinth had no blood aristocracy, she had a definite social ladder with rungs comprised of wealth, connections, and prestige.

Melting pot of the gods.

In addition to being a melting pot for people, Corinth was a melting pot for gods. She celebrated Greek and Roman gods including Apollo, Aphrodite/Venus, Asclepius, Athena, Demeter and Kore, Dionysus, Artemis, Hera Acraea, Hermes/Mercury, Jupiter/Zeus, Poseidon/Neptune, Tyche, and Fortuna, as well as Egyptian mystery cults such as the worship of Isis, and she had an absolute fascination with all things pertaining to magic and the supernatural.

Into spirituality and inclusiveness.

Most Corinthians incorporated as many gods as possible into their lifestyles and were always open to new gods and spiritual experiences. The more gods or higher powers one could include in one’s lifestyle, the deeper and more well-rounded a person was. This was the new wave of the Hellenistic world. The temple of Demeter in Pergammum, for example, also had altars to Hermes, Helios, Zeus, Asclepius, and Heracles. And the private chapel of Emperor Severus in the 3d Century contained shrines to Orpheus, Abraham, Apollonius, and Jesus. It is not unusual to find ancient inscriptions or written fragments in the which the author says something like, “I pray to all gods,” or “We magnify every god.” Many welcomed new and strange gods, for they offered the stimulation of the “new and different” – a phenomenon mentioned by Luke when describing Athens in Acts 17. It was never a problem to include more gods, but only to exclude, and this is where the Christians ran into trouble. They believed in the one true God, the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, and rejected all other gods as phony.

Haters of humanity.

Christians were labeled “misanthropes,” haters of humanity, because they refused to join in the worship and sacrificial meals offered to local, traditional gods and in the festivals that pumped up local pride or helped polish a city’s image as loyal to the emperor by taking part in the imperial cult. Christian exclusiveness was viewed as a social problem, a threat to peace and harmony. It wasn’t a problem that Christians had a new and different god, but only that their god didn’t play well with the other gods. It wasn’t a problem that Christians had a new religious experience, but only that their religion was “better than everyone else’s.”

Corinth revivitus.

This, too, is increasingly the situation in modern day America. We don’t call it polytheism, but that’s what it is. Increasingly, American’s live narcissistic lives in private spheres of reality, and they incorporate an ever changing array of faiths, higher powers, and spiritual experiences as they remake themselves and their private realities over and over again. As in Corinth, Christians are increasingly labeled as “haters,” and Christian teaching is labeled as “hate speech.” Christians are not “inclusive.”

The imperial faith.

How do you hold society together in such a radically individualistic environment? What provides the glue? You must have an overarching faith that encompasses all the other faiths and governs the public square in a way that keeps the peace and prosperity which are requisite for such a high order of me-worship. In the 1st century, that overarching faith was faith in the Empire itself. All people were expected to worship the genius of the Emperor, the living embodiment of the spirit, values, and greatness of Rome.

Rome to the world.

This was another thing that added to Corinth’s prestige – she was a Roman colony, designated by Julius Caesar himself in 46 BC. As such, Corinth was to be Rome to the world – a shining city on a hill to display and promote the grace and peace that Rome offered to the world. Consistent with her calling, Corinth’s proudest temple, towering over all others, the only one you could see from the forum, rising up over its western wall, was the imperial temple. The imperial cult in the 1st century was spreading through the empire much more rapidly than Christianity.

The Corinthian church.

Into this environment came the Apostle Paul and established the Corinthian church, which at the time of Paul’s letter consisted of about 100 members (according to one scholar’s estimate). Looking up at Caesar’s temple, living in Caesar’s city, who was the Corinthian Church, a mere 100 believers, against so dominant a force? Everything worked according to Caesar’s values – the politics, the economy, social relations, everything. How were they supposed to subsume the Empire, when they were, it seemed, so totally subsumed by it? Yet, Paul tells them their identity is totally shaped by Christ. They are his assembly, his fellowship (1Co 1.2a, 9). They are shaped by his word and live by his law (1.2b, d). They seek his favor and blessing (1.3). They purvey his culture and values.

Seemingly benign words.

Paul’s opening words look benign to us, but they were anything but benign in the 1st century. Everything Paul says puts Jesus in direct competition with Caesar, and the Corinthian church in direct competition with the imperial cult (and thus with Corinth as a Roman colony). “Church” (ekklesia, lit. “assembly”) was used of all the cults and societies of the empire, including the imperial cult, as well as the gathered representatives of local government. “Lord” was Caesar’s title (there were many gods and powers but one lord, Caesar). All Romans were united, despite race, language, and local gods, by the fact that they “called on the name” of Caesar. “Grace and peace” were what Caesar brought to the world.

Praise.

Paul praises God for enriching the Corinthians (1.5, 7) instead of offering the normal praises found in ancient letters to citizens of Corinth – praises for Corinth’s situation, beauty, and greatness, and her privilege as a colony of Rome.

Promise.

Paul tells them that they will before long see an “eagerly [a]wait[ed] . . . revelation” of Christ, the “day of Christ” (1.7b, 8b). They will see the fulfillment of Jesus’ prophesy that Christ-rejecting Jerusalem would get worse and worse and ultimately be destroyed by foreign armies in 70AD. They will see proof that Jesus reigns over the world and history – proof that Jesus has all power and authority and all judgment committed to him. They will see how it is that they are more powerful than the Roman Empire. They will see that it isn’t about what they as 100 Christians can do. It is about what Christ can do.

Threat.

But we also see a threat to the work of Christ in the Corinthian’s midst. That threat isn’t from outside; it’s from inside. Just as the bigger challenge in the OT was not getting Israel out of Egypt but getting Egypt out of Israel, so the bigger challenge with the Corinthians was getting the Empire out of them.

Silence.

Paul signals the problem in his opening. He praises God for the Corinthians’ knowledge, gifts, and talents (1.5, 7) – they were legit – but he says not one word of praise for the Corinthians themselves – for their labors, for their lives, for their fruit. (Compare Paul’s opening remarks to the Colossians and Thessalonians (Col 1.3-4; 1Th 1.3, 7).)

True spirituality.

Paul is signaling through his silence what he will shortly make explicit through his words: Having spiritual gifts doesn’t mean you are spiritual. Having spiritual knowledge doesn’t mean you are spiritual. Having talent and abilities doesn’t mean you are spiritual. The Corinthians’ knowledge, talents, and gifts were being contextualized and undermined by the world’s way of life coming through in their attitudes, especially in their attitudes toward one another. The fact that they were so gifted, so talented, so knowledgeable, was deceiving them as to their true state. Spirituality is measured in term of fruit. Maturity is measured in terms of fruit. Power is measured in terms of fruit. Christ’s pleasure in us is measure in terms of fruit. Christ’s willingness to do great things through us is measured in terms of fruit.

The thing about fruit.

There’s no work or credit in gifts – that’s why they’re called gifts. But fruit is different. While there is no work or merit in fruit, there is dying in fruit, for “a seed does not bear fruit unless it goes into the ground and dies (1Co 15.36).” While fruit is the natural result of abiding in Christ, abiding in Christ means following him in death and resurrection. Fruit is the result of being made like Christ, of dying to ourselves, of saying “not my will,” of losing our lives for Christ’s sake. And this is what the Corinthians were missing. And as a result, everything was at risk – the power of Christ in and through them to the world, the joy, peace, and unity of Christ upon them. They were missing out, and the world was missing out because of them.

What about us?

The median size of American churches is about the same size as the Corinthian church. We live in a culture more and more like Corinth. We have the same calling as the Corinthian church. What would Paul write to us? I fear he would write exactly what he did to the Corinthians. I fear he would praise God for our gifts, our knowledge, our talent, and would be utterly silent about our fruit — our love, our unity, our Christlikeness. The ancient world desperately needed the Corinthian Christians to become Christ for its sake, and our world desperately needs us to become Christ for its sake.